The Wayland core protocol has described surface state updates the same way since the beginning: requests modify pending state, commits either apply that state immediately or cache it into the parent for synchronized subsurfaces. Compositors implemented this model faithfully. Then things changed.

The problem emerged from GPU work timing. When a client commits a surface with a buffer, that buffer might still have GPU rendering in progress. If the compositor applies the commit immediately, it would display incomplete content—glitches. If the compositor submits its own GPU work with a dependency on the unfinished client work, it risks missing the deadlines for the next display refresh cycles and even worse stalling in some edge cases.

To get predictable timing, the compositor needs to defer applying commits until the GPU work finishes. This requires tracking readiness constraints on committed state.

Mutter was the first compositor to address this by implementing constraints and dependency tracking of content updates internally. Instead of immediately applying or caching commits, Mutter queued the changes in what we now call content updates, and only applied them when ready. Critically, this was an internal implementation detail. From the client’s perspective, the protocol semantics remained unchanged. Mutter had deviated from the implementation model implied by the specification while maintaining the observable behavior.

When we wanted better frame timing control and a proper FIFO presentation modes on Wayland, we suddenly required explicit queuing of content updates to describe the behavior of the protocols. You can’t implement FIFO and scheduling of content updates without a queue, so both the fifo and commit-timing protocols were designed around the assumption that compositors maintain per-surface queues of content updates.

These protocols were implemented in compositors on top of their internal queue-based architectures, and added to wayland-protocols. But the core protocol specification was never updated. It still described the old “apply or cache into parent state” model that has no notion of content updates, and per-surface queues.

We now had a situation where the core protocol described one model, extension protocols assumed a different model, and compositors implemented something that sort of bridged both.

That situation is not ideal: If the internal implementation follows the design which the core protocol implies, you can’t deal properly with pending client GPU work, and you can’t properly implement the latest timing protocols. To understand and implement the per-surface queue model, you would have to read a whole bunch of discussions, and most likely an implementation such as the one in mutter. The implementations in compositors also evolved organically, making them more complex than they actually have to be. To make matter worse, we also lacked a shared vocabulary for discussing the behavior.

The obvious solution to this is specifying a general model of the per-surface content update queues in the core protocol. Easier said than done though. Coming up with a model that is sufficient to describe the new behavior while also being compatible with the old behavior when no constraints on content updates defer their application was harder than I expected.

Together with Julian Orth, we managed to change the Wayland core protocol, and I wrote documentation about the system.

Recently Pekka Paalanen and Julian Orth reviewed the work, which allowed it to land. The updated and improved Wayland book should get deployed soon, as well.

The end result is that if you ever have to write a Wayland compositor, one of the trickier parts to get right should now be almost trivial. Implement the rules as specified, and things should just work. Edge cases are handled by the general rules rather than requiring special knowledge.

A wild blog appears…

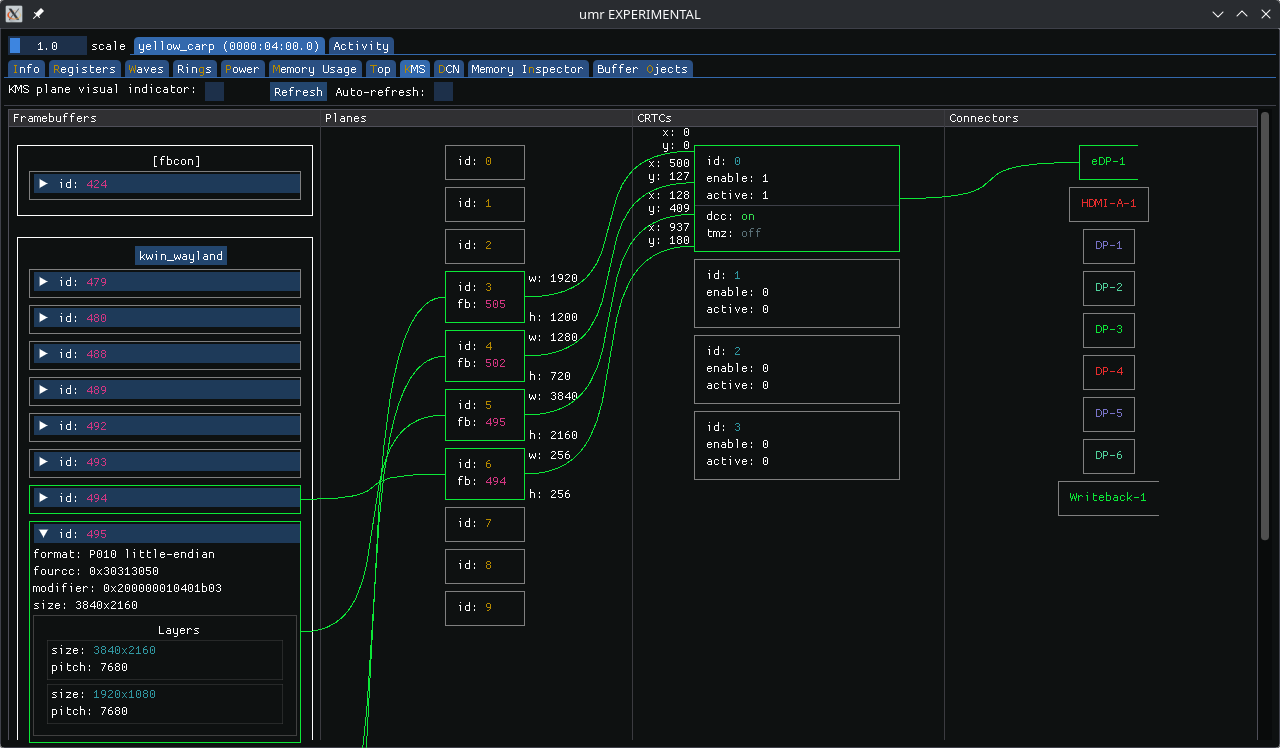

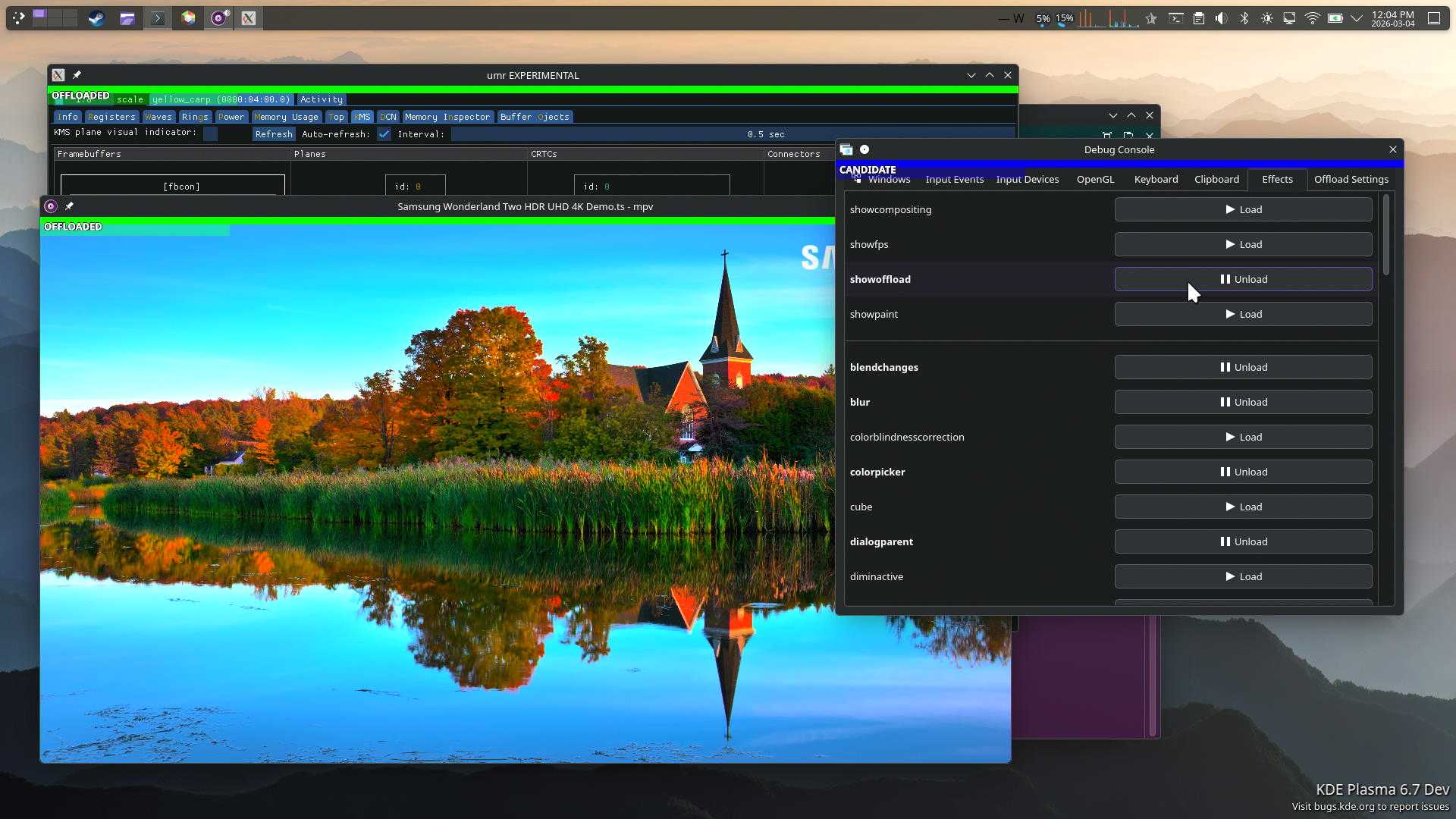

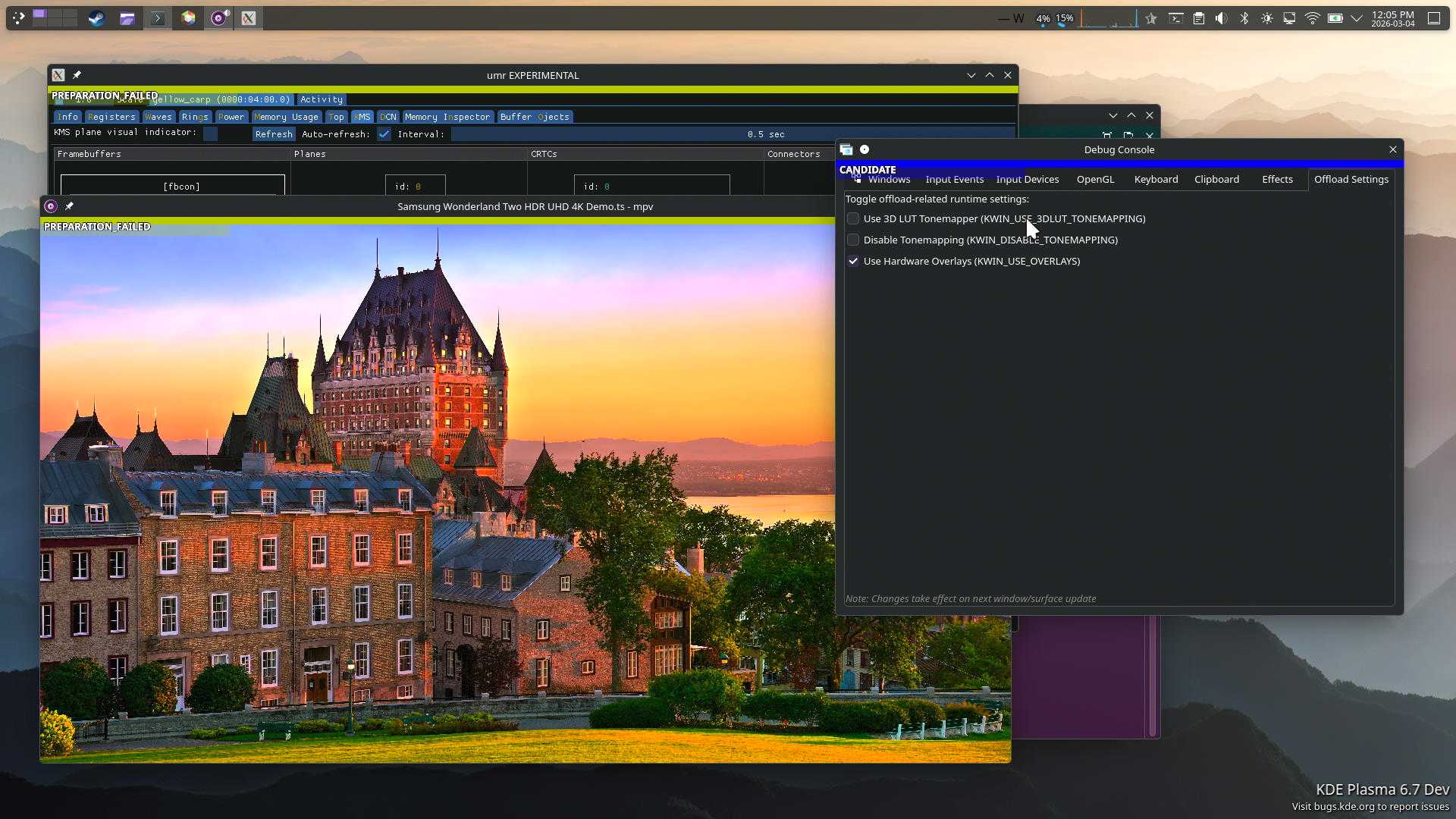

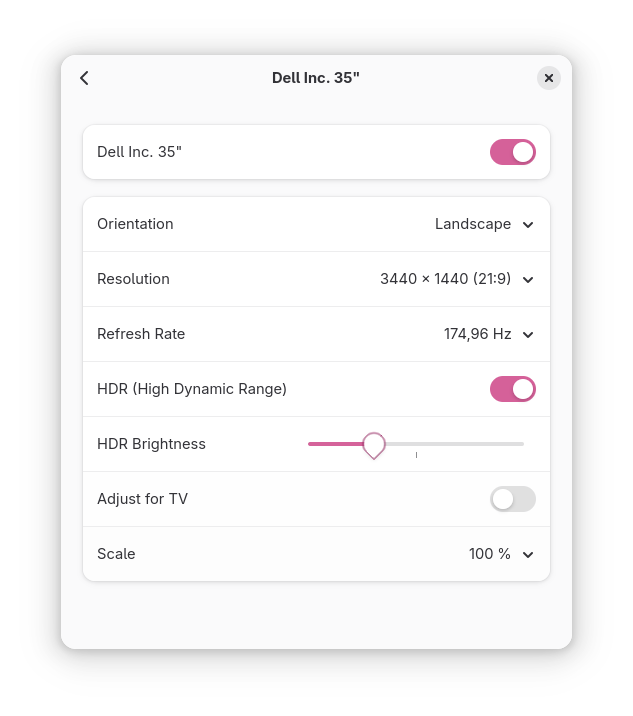

A couple months ago the DRM/KMS Plane Color Pipeline API was merged after more than 2 years of work and deep discussions. Many people worked on it and it’s nice to see it upstream. KWin and other compositors implemented support for it. I’ll mainly focus on kwin here because that’s what I use regularly and what I am most familiar with. I will also focus on AMD HW because that’s what I’m working on.

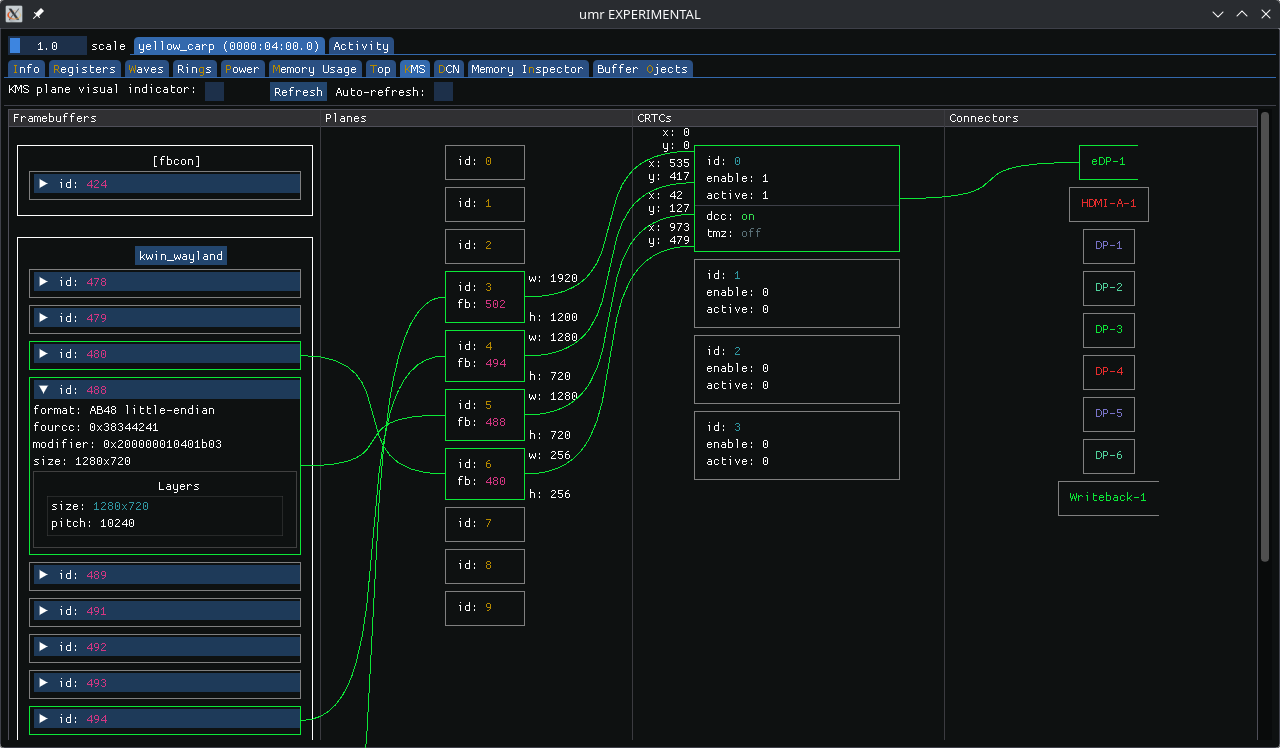

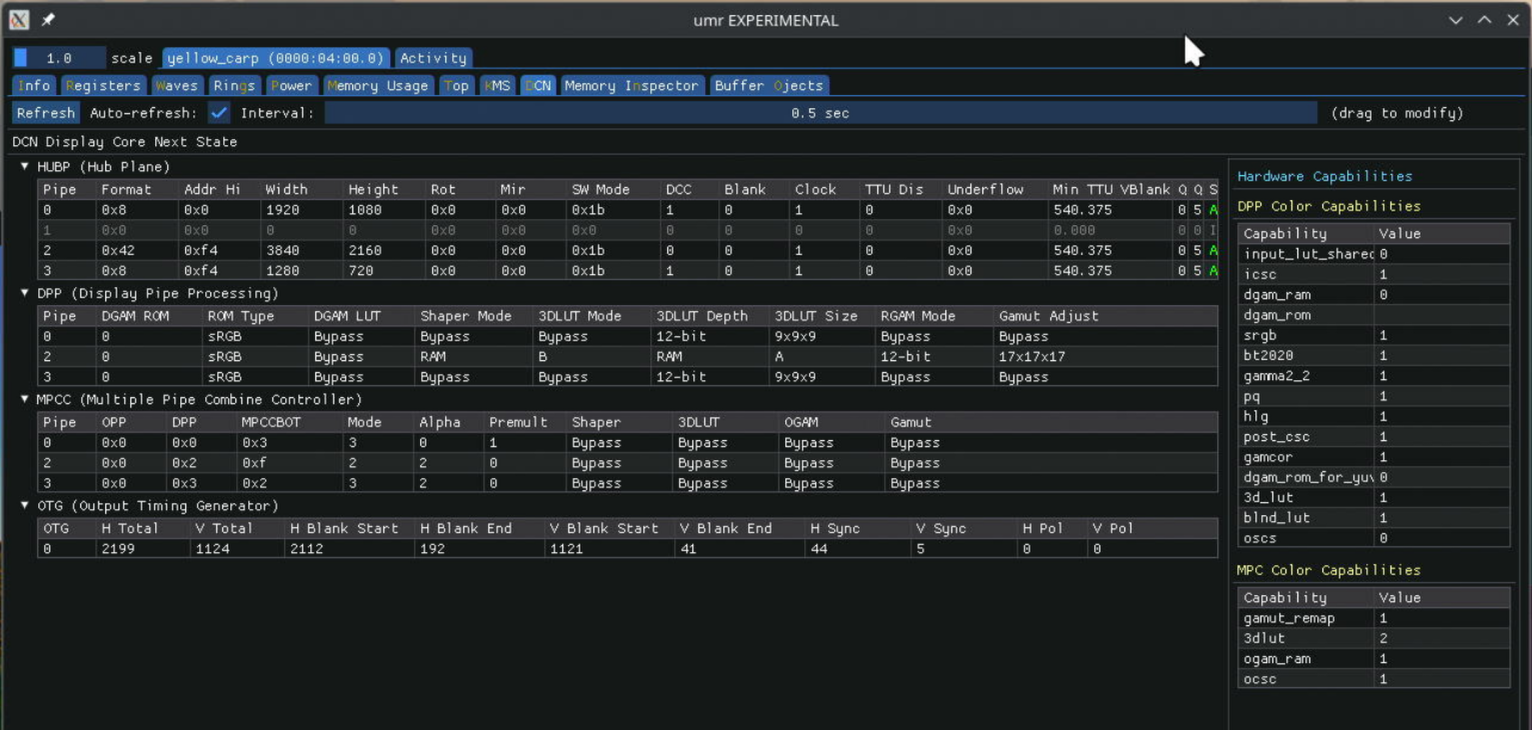

On AMD HW with a kernel that includes the new Color Pipeline API KWin enables HW composition for surfaces that update more than 20 times per second on a single enabled display. It needs a few other things to match as well. In particular, this means that running mpv with the default backend (--vo=gpu) will use HW composition for mpv’s video surface with the rest of the desktop. The easiest way to observe this is with UMR by running it in --gui mode and looking at the KMS tab.

In my examples UMR also gets HW composed, so this shows 4 planes:

The mpv framebuffer shows up as an AB48 buffer, not NV12. This is because the --vo=gpu backend in mpv performs any required color-space conversation, scaling, and tone-mapping, and then offers up a 16-bpc buffer to the Wayland compositor, which kwin passes to the DRM/KMS driver.

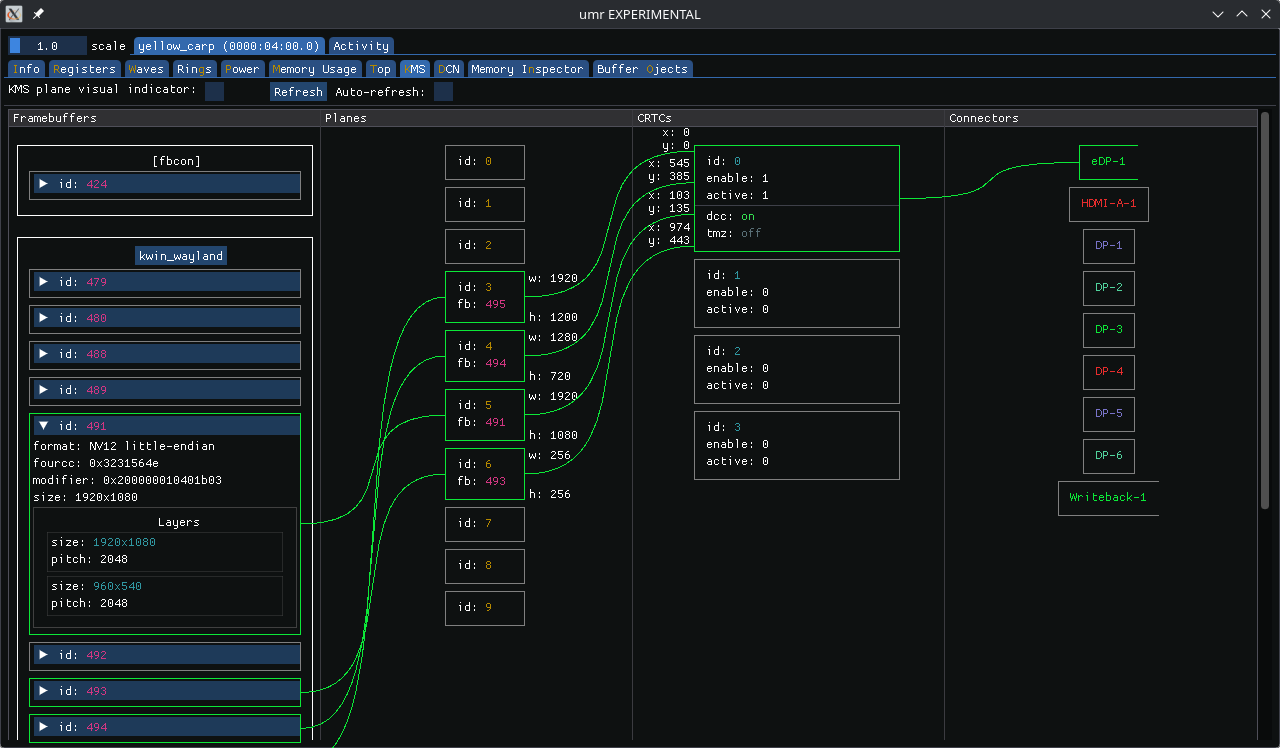

We can tell mpv to pass the raw YUV buffer (NV12 or P010) to kwin by passing using the --vo=dmabuf-wayland backend. This tells mpv to simply decode the video stream but leave the buffer alone. It then passes the buffer information to kwin via the Wayland color-management and color-representation protocol extensions.

When we do this we don’t see a HW-composed plane in umr. KWin color-space converts, scales, tone-maps, and composes the plane via OpenGL. It can’t offload it to display HW because the DRM color pipeline API doesn’t yet support color-space conversion (CSC). The drm_plane does have COLOR_RANGE and COLOR_ENCODING properties to specify CSC, but they are deprecated with the color pipeline API.

So I went and implemented a CSC drm_colorop, added IGT tests and added support for it in kwin.

With this new CSC colorop we now see an NV12 buffer for our SDR video (I’m using a 1080p60 Big Buck Bunny clip).

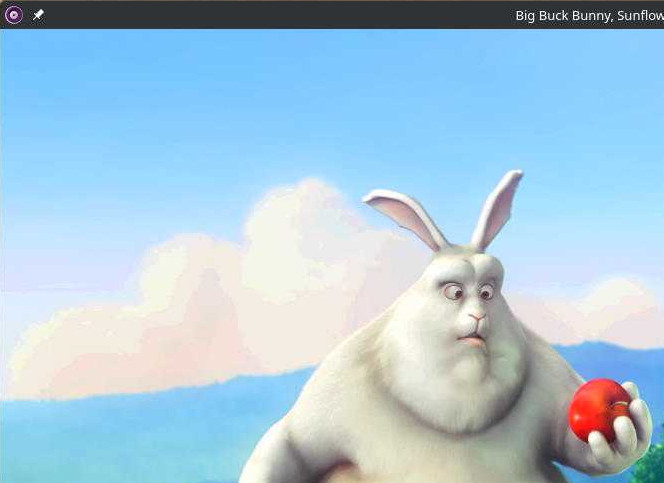

Unfortunately we see some banding during the HW composed Big Buck Bunny playback:

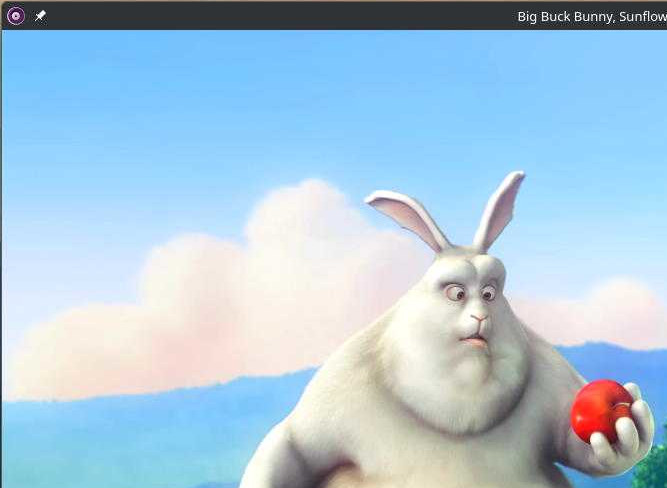

This is the SW composed version, showing no problems:

I haven’t yet debugged the banding. It seems to happen with one of the 1D LUTs.

But the AMD HW also has a 3D LUT and kwin lets us sample its entire internal color pipeline, so we can simply sample it at our 3DLUT coordinates and program it to HW. This allows us to represent any complex color pipeline with a single 3D LUT operation. The result is this.

In order to compose HDR content kwin creates a tone-mapper. By packing the entire color pipeline into a 3D LUT we don’t need to worry about it and get support for HW composition of HDR content for free.

Note: AMD’s 3D LUT uses 17 entries per dimension and interpolates tetrahedrally. This will give good results when applied in non-linear luminance space. KWin blends in non-linear space, and the input buffer is non-linear, so it works well here. While this gives good results you might still observe minor differences, especially in brighter areas of the image. This can be observed when toggling between HW and SW composition in certain scenes.

Because AMD’s DCN HW uses a multi-tap scaler filter but kwin’s SW composition uses GL_LINEAR there are differences in scaling. It’s apparent when doing 4-to-1 downscaling, such as when scaling this 4k (HDR) video down to 720p.

SW composed:

HW composed:

The former has stronger aliasing. The latter looks softer and more natural, in my opinion. The difference becomes much less pronounced when the image is downscaled less, e.g., from 4k to 1080p.

At this point there is no good API to help align the two. GL seems to only have GL_NEAREST and GL_LINEAR when not dealing with mipmaps. DRM/KMS provides “Default” and “Nearest Neighbor” via the SCALING_FILTER property. While this allows us to use a nearest neighbor filter in both cases that’s undesirable since it’ll make the image worse in both cases.

When I started this work I asked myself: How do I see whether a surface is a candidate for offloading? How do I see which actual surface is being offloaded?

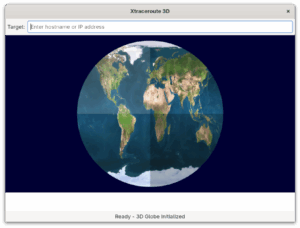

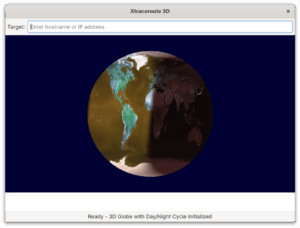

To solve this I worked with Claude to create a plugin that marks surfaces and their offload status:

It’s quite useful to see immediately which surfaces are candidates, and why they might fail to offload.

I’ve also added a new tab to dynamically toggle HW composition and and off. The screenshot shows toggles for 3D LUT and tone-mapping and while we can add those as well they don’t always take effect as expected, so I left them out of the branch that’s linked below. But the ability to toggle HW composition is quite powerful when debugging HW composition issues.

kwin branch on top of csc-3dlut branch

DCN HW programming can be logged via the amdgpu_dm_dtn_log debug log debugfs. But that log is quite extensive. It can be useful to show this in UMR with auto-update functionality to see programmed settings immediately.

The code still needs a fair bit of work as this was the first time I used Claude for something extensive like this. I plan to post it eventually.

I used Claude Sonnet extensively for this work (it basically wrote all the code), so I thought it prudent to leave a couple thoughts on it.

LLMs are large language models, not actual artificial intelligence. They’re language models, and are designed to work well with language. They’re large and can hold much more context than humans. Use them in ways that uses their strength. I’ve found value in understanding complex code-bases, and creating code that fits within those code-bases.

Don’t stop owning your code. Even if it’s produced by an LLM, take pride and ownership. This means, review what you get from an LLM. Be active in steering it. Don’t throw trash at maintainers. Your name and reputation are on the line.

I’ll be working with relevant communities and maintainers to attempt to upstream these things.

The CSC colorop is probably in a good shape.

The KWin code requires feedback from maintainers. I expect it will need more work.

This also needs more testing. At times I see the 3D LUT fail to apply. I’m not sure whether this is a problem with my kwin code or amdgpu.

I don’t see offload candidate surfaces from many applications where I’d expect to see them. This needs further analysis. For one, I’m unsure what happens with games. The other thing is Youtube in Firefox, which fails to present the video as an offload surface. Some other videos work fine in Firefox, in particular local video playback.

sneaky edit: and power measurements, of course, since that’s the entire reason for this.

Hi all!

Lars has contributed an implementation independent test suite for the scfg configuration file format. This is quite nice for implementors, they get a base test suite for free. I’ve added support for it for libscfg, the C implementation.

I’ve spent some time working on the go-proxyproto library. While adding

support for PP2_SUBTYPE_SSL_CLIENT_CERT (a PROXY protocol addition to carry

the TLS client certificate I’ve introduced last month), I’ve fixed large PROXY

protocol headers being rejected (TLS certificates can be a few kilobytes), I’ve

fixed some issues in the test suite, and I’ve improved the HTTP/2 helper. I’ve

merged support for PP2_SUBTYPE_SSL_CLIENT_CERT in tlstunnel, soju and

kimchi.

Speaking about soju, delthas and taiite have finished up soju.im/client-cert,

a new IRC extension to manage TLS client certificates. Clients can register,

unregister, and list TLS client certificates which can be used for

authentication for the logged in user. We aim to stop storing plaintext

passwords, instead generating a fresh TLS certificate when logging in for the

first time and storing its key. Nobody has started working on a Goguma patch

yet, but that would be nice!

Goguma now has a brand new shiny website! Many thanks to Jean

THOMAS for building it from the ground up. delthas has added a /invite

command, I’ve added support for removing reactions (via the new unreact

message tag), and I’ve experimented with a Web build of the app (just for fun,

with WebSockets connections instead of TCP).

kanshi v1.9 has been released. This new version is the first to leverage

vali for Varlink support. The new ...output directive can match any number

of outputs, a the new mode preferred output directive can be used to select

the mode marked as preferred by the kernel.

I’ve resumed work on oembed-proxy, a small server which generates oEmbed

previews for arbitrary URLs. It’s quite simple: send an HTTP request with a

URL, it replies with a JSON payload with metadata such as page title, image

size, and so on. I plan to use it for IRC clients, to show link previews

without leaking the client’s IP address and to make them work on Web clients.

I’ve added support for Open Graph, the most widely used scheme to attach

structured data to Web pages. I ended up linking with ffmpeg because I figured

I would need to eventually generate thumbnails for images and videos. I played

a bit with CGo to integrate Go’s streaming io.Reader with ffmpeg’s C API. I

had to jump through a few hoops, but it works!

Hiroaki Yamamoto has contributed wlroots support for ext-workspace-v1, and Félix Poisot has upgraded color-management-v1 to minor version 2. Félix also uncovered some holes in our explicit synchronization implementation — we’re in the process of fixing these up now. I’ve started the wlroots release candidate cycle, and I just published RC3 today.

I’ve spent quite some time improving go-kdfs, a Go library for the Khronos

Data Format Specification. KDFS defines a standard file format to describe

how pixels are laid out in memory and how their contents should be interpreted.

I’ve added a bunch of new pixel formats, JSON output for the CLI, unit tests

against dfdutils, and a lot of other smaller improvements. I’ve written a

wlroots patch to remove a bunch of manually written pixel format

tables an replace them with auto-generated tables from go-kdfs. I’ve also added

sample position to pixfmtdb, a Web frontend for go-kdfs (see for instance the

Y samples on the DRM_FORMAT_NV12 page). Next up, I’d like to add missing

features to the kdfs compat command so that wlroots can get rid of all of its

tables (better endianness support, and flags to specify/strip some information

such as the alpha channel, color primaries or transfer function).

I’m quite happy with all of the good stuff we’ve managed to get over the fence this month! See you in March!

This is the start of a series about getting OpenGL ES 3.0 conformance on Vivante GC7000 hardware using the open-source etnaviv driver in Mesa. Thanks to Igalia for giving me the opportunity to spend some time on these topics.

etnaviv has supported GLES2 on Vivante GPUs for a long time. GLES3 support has been progressing steadily, but the remaining dEQP failures are the stubborn ones - the cases where the hardware doesn’t quite do what the spec says, and the driver has to get creative.

This topic came up at kernel maintainers summit and some other groups have been playing around with it, particularly the BPF folks, and Chris Mason's work on kernel review prompts[1] for regressions. Red Hat have asked engineers to investigate some workflow enhancements with AI tooling, so I decided to let the vibecoding off the leash.

My main goal:

- Provide AI led patch review for drm patches

- Don't pollute the mailing list with them at least initially.

This led me to wanting to use lei/b4 tools, and public-inbox. If I could push the patches with message-ids and the review reply to a public-inbox I could just publish that and point people at it, and they could consume it using lei into their favorite mbox or browse it on the web.

I got claude to run with this idea, and it produced a project [2] that I've been refining for a couple of days.

I started with trying to use Chris' prompts, but screwed that up a bit due to sandboxing, but then I started iterating on using them and diverged.

The prompts are very directed at regression testing and single patch review, the patches get applied one-by-one to the tree, and the top patch gets the exhaustive regression testing. I realised I probably can't afford this, but it's also not exactly what I want.

I wanted a review of the overall series, but also a deeper per-patch review. I didn't really want to have to apply them to a tree, as drm patches are often difficult to figure out the base tree for them. I did want to give claude access to a drm-next tree so it could try apply patches, and if it worked it might increase the review, but if not it would fallback to just using the tree as a reference.

Some holes claude fell into, claude when run in batch mode has limits on turns it can take (opening patch files and opening kernel files for reference etc), giving it a large context can sometimes not leave it enough space to finish reviews on large patch series. It tried to inline patches into the prompt before I pointed out that would be bad, it tried to use the review instructions and open a lot of drm files, which ran out of turns. In the end I asked it to summarise the review prompts with some drm specific bits, and produce a working prompt. I'm sure there is plenty of tuning left to do with it.

Anyways I'm having my local claude run the poll loop every so often and processing new patches from the list. The results end up in the public-inbox[3], thanks to Benjamin Tissoires for setting up the git to public-inbox webhook.

I'd like for patch submitters to use this for some initial feedback, but it's also something that you should feel free to ignore, but I think if we find regressions in the reviews and they've been ignored, then I'll started suggesting it stronger. I don't expect reviewers to review it unless they want to. It was also suggested that perhaps I could fold in review replies as they happen into another review, and this might have some value, but I haven't written it yet. If on the initial review of a patch there is replies it will parse them, but won't do it later.

[1] https://github.com/masoncl/review-prompts

[2] https://gitlab.freedesktop.org/airlied/patch-reviewer

[3] https://lore.gitlab.freedesktop.org/drm-ai-reviews/

After years of working on etnaviv - a Gallium/OpenGL driver for Vivante GPUs - I’ve been wanting to get into Vulkan. As part of my work at Igalia, the goal was to bring VK_EXT_blend_operation_advanced to lavapipe. But rather than going straight there, I started with Honeykrisp - the Vulkan driver for Apple Silicon - as a first target: a real hardware driver to validate the implementation against before wiring it up in a software renderer. My first Vulkan extension, and my first real contribution to Honeykrisp.

If you haven't heard of gastown it is my sincere pleasure to be the one to fix that. If you're like me and you have way more ideas than time or ability to type them, gastown is an absolute game changer. I haven't felt this jazzed about programming in decades, like, I'm using antiquated slang like "jazzed" without embarrassment.

Well. Not embarrassment about that.

I awoke to a polite note from a colleague saying I had apparently pushed a bunch of random branches to the upstream Mesa repo and are we sure I wasn't hacked. No, I wasn't, those branches were definitely things I was working on, but I had been working on them locally, nothing should have even been pushed to my personal gitlab repo. I was using gastown to do that work so obviously we start looking there...

Gastown is built on beads and beads is built on git. Every atom of work within a gastown has a bead, which means updates to those beads are absolutely critical, if they don't happen then the town chugs to a halt. Gastown is also built on claude, or whatever, but claude is what I was using. Not to pick on claude, here, just using it as a generic brand name, claude is too polite to be a robust tool, sometimes. It'll lose some critical bit of context and want to stop and ask for directions. For a coding assistant that's a great way to be; for a code factory it's less awesome. It is slightly comic to read how much of gastown is just different ways of exhorting a lilypond of claudes to please do their work, please.

In gastown you wrap an upstream project in a rig, and I'm an old so I have all my git clones of everything already in ~/git, so I had set up my rigs to use those as the local storage so I didn't have to wait for things to clone again. The town mayor or one of his underlings dispatches work to ephemeral claude instances by writing the orders down in a bead, the work happens in the worker instance's git worktree instance of the rig. I would use gastown for the automagic git worktree management alone, forget the rest of the automation.

But here's where the projectile weapon starts pointing towards the positive gradient of the ol' G field. One way to try to help when claude loses context is to put important orientation information into CLAUDE.md, and helpfully, the /init command will build that for you by inspecting the current project. So I ran that at the top level of my gastown so it, gastown, wouldn't have to keep parsing "gt --help" output just to rediscover how to update a bead, hopefully. In doing so, claude lifted that directive about bead updates being seriously no-kidding mandatory up to the top level.

From that point on, claude instances would interpret that directive to apply to the project in the rig! So now, work isn't done until the work-in-progress branch is pushed. Until it is pushed to origin. Which, too bad that you cloned it from https, I'm going to discover the ssh URL to your personal mesa repo from the local repo's git config and change the URL in the rig to use ssh, because I was told to resolve the push failure or else.

So, cautionary tale, right? Maybe determinism in your tools still has value. Maybe plaintext English isn't the best idea for a configuration language. Maybe agent prompts need to be extra careful about context. Maybe careful sandbox construction would mitigate that kind of escape. Maybe an open source agent would be more trustworthy in terms of configurable tool usage since you would actually be able to see and control the boundary instead of just trusting that there is a boundary at all.

Just to keep up some blogging content, I'll do where did I spend/waste time last couple of weeks.

I was working on two nouveau kernel bugs in parallel (in between whatever else I was doing).

Bug 1: Lyude, 2 or 3 weeks ago identified the RTX6000 Ada GPU wasn't resuming from suspend. I plugged in my one and indeed it wasn't. Turned out since we moved to 570 firmware, this has been broken. We started digging down various holes on what changed, sent NVIDIA debug traces to decode for us. NVIDIA identified that suspend was actually failing but the result wasn't getting propogated up. At least the opengpu driver was working properly.

I started writing patches for all the various differences between nouveau and opengpu in terms of what we send to the firmware, but none of them were making a difference.

I took a tangent, and decided to try and drop the latest 570.207 firmware into place instead of 570.144. NVIDIA have made attempts to keep the firmware in one stream more ABI stable. 570.207 failed to suspend, but for a different reason.

It turns out GSP RPC messages have two levels of sequence numbering, one on the command queue, and one on the RPC. We weren't filling in the RPC one, and somewhere in the later 570's someone found a reason to care. Now it turned out whenever we boot on 570 firmware we get a bunch of async msgs from GSP, with the word ASSERT in them with no additional info. Looks like at least some of those messages were due to our missing sequence numbers and fixing that stopped those.

And then? still didn't suspend/resume. Dug into memory allocations, framebuffer suspend/resume allocations. Until Milos on discord said you did confirm the INTERNAL_FBSR_INIT packet is the same, and indeed it wasn't. There is a flag bEnteringGCOff, which you set if you are entering into graphics off suspend state, however for normal suspend/resume instead of runtime suspend/resume, we shouldn't tell the firmware we are going to gcoff for some reason. Fixing that fixed suspend/resume.

While I was head down on fixing this, the bug trickled up into a few other places and I had complaints from a laptop vendor and RH internal QA all lined up when I found the fix. The fix is now in drm-misc-fixes.

Bug 2: A while ago Mary, a nouveau developer, enabled larger pages support in the kernel/mesa for nouveau/nvk. This enables a number of cool things like compression and gives good speedups for games. However Mel, another nvk developer reported random page faults running Vulkan CTS with large pages enabled. Mary produced a workaround which would have violated some locking rules, but showed that there was some race in the page table reference counting.

NVIDIA GPUs post pascal, have a concept of a dual page table. At the 64k level you can have two tables, one with 64K entries, and one with 4K entries, and the addresses of both are put in the page directory. The hardware then uses the state of entries in the 64k pages to decide what to do with the 4k entries. nouveau creates these 4k/64k tables dynamically and reference counts them. However the nouveau code was written pre VMBIND, and fully expected the operation ordering to be reference/map/unmap/unreference, and we would always do a complete cycle on 4k before moving to 64k and vice versa. However VMBIND means we delay unrefs to a safe place, which might be after refs happen. Fun things like ref 4k, map 4k, unmap 4k, ref 64k, map 64k, unref 4k, unmap 64k, unref 64k can happen, and the code just wasn't ready to handle those. Unref on 4k would sometimes overwrite the entry in the 64k table to invalid, even when it was valid. This took a lot of thought and 5 or 6 iterations on ideas before we stopped seeing fails. In the end the main things were to reference count the 4k/64k ref/unref separately, but also the last thing to do a map operation owned the 64k entry, which should conform to how userspace uses this interface.

The fixes for this are now in drm-misc-next-fixes.

Thanks to everyone who helped, Lyude/Milos on the suspend/resume, Mary/Mel on the page tables.

Mesa 26.0 is big for RADV’s ray tracing. In fact, it’s so big it single-handedly revived this blog.

There are a lot of improvements to talk about, and some of them were in the making for a little over two years at this point.

In this blog post I’ll focus on the things I myself worked on specifically, most of which revolve around how ray tracing pipelines are compiled and dispatched. Of course, there’s more than just what I did myself: Konstantin Seurer worked on a lot of very cool improvements to how we build BVHs, the data structure that RT hardware uses for the triangle soup making up the geometry in game scenes so the HW can trace rays against them efficiently.

The rest of this blog post will assume some basic idea of how GPU ray tracing and ray tracing pipelines work. I’ve written about this in more detail one-and-a-half years ago, in my blog post about RT pipeline being enabled by default.

Let’s take a bit of a closer look at what I said about RT pipelines in RADV back then. In a footnote, I said:

Any-hit and Intersection shaders are still combined into a single traversal shader. This still shows some of the disadvantages of the combined shader method, but generally compile times aren’t that ludicrous anymore.

I spent a significant amount of time in that blogpost detailing about how there tend to be a really large number of shaders, and combining them into a single megashader is very slow because shader sizes get genuinely ridiculous at that point.

So clearly, it was only a matter of time until the any-hit/intersection shader combination would blow up spectacularly on a spectacular number of shaders, as well.

For illustrating the issues with inlined any-hit/intersection shaders, I’ll use Unreal Engine as an example because I noticed it being particularly egregious here. This definitely was an issue with other RT games/workloads as well, and function calls will provide improvements there too.

There’s a lot of people going around making fun of Unreal Engine these days, to the point of entire social media presences being built around mocking the ways in which UE is inefficient, slow, badly-designed bloatware and whatnot. Unfortunately, the most popular critics often know the least what they’re actually talking about. I feel compelled to point out here that while there certainly are reasonable complaints to be raised about UE and games made with it, I explicitly don’t want this section (or anything else in this post, really) to be misconstrued as “UE doing a bad thing”. As you’ll see, Unreal is really just using the RT pipeline API as designed.

With the disclaimer aside, what does Unreal actually do here that made RADV fall over so hard?

Let’s talk a bit about how big game engines handle shading and materials. As you’ll probably know already, to calculate how lighting interacts with objects in a scene, an application will usually run small programs called “shaders” on the GPU that, among other things1, calculate the colors different pixels have according to the material at that pixel.

Different materials interact with light differently, and in a large world with tons of different materials, you might end up having a ton of different shaders.

In a traditional raster setup you draw each object separately, so you can compile a lot of graphics pipelines for all of your materials, and then bind the correct one whenever you draw something with that material.

However, this approach falls apart in ray tracing. Rays can shoot through the scene randomly and they can hit pretty much any object that’s loaded in at the moment. You can only ever use one ray tracing pipeline at once, so every single material that exists in your scene and may be hit by a ray needs to be present in the RT pipeline. The more materials a game has, the more ludicrous the number of shaders gets.

Usually, this is most relevant for closest-hit shaders, because these are the shaders that get called for the object hit by the ray (where shading needs to be calculated). However, depending on your material setup, you may have something like translucent materials - where parts of the material are “see-through”, and rays should go through these parts to reveal the scene behind it instead of stopping.

This is where any-hit shaders come into play - any-hit shaders can instruct the driver to ignore a ray hitting a geometry, and instead keep searching for the next hit. If you have a ton of (potentially) translucent materials, that would translate into a lot of any-hit shaders being compiled for these materials.

The design of RT pipelines is quite obviously written in a way that accounts for this. In the previous blogpost I already mentioned pipeline libraries - the idea is that a material could just be contained in a “library”, and if RT pipelines want to use it, they just need to link to the library instead of compiling the shading code all over again. This also allows for easy addition/removal of materials: Even though you have to re-create the RT pipeline, all you need to do is link to the already compiled libraries for the different materials.

UE, particularly UE4, is a heavy user of libraries, which makes a lot of sense: It maps very well to what it’s trying to achieve. Everything’s good, as long as the driver doesn’t do silly things.

Silly things like, for example, combining any-hit shaders into one big traversal shader.

Doing something like that pretty much entirely side-steps the point of libraries. The traversal shader can only be compiled when all any-hit shaders are known, which is only at the very final linking step, which is supposed to be very fast…

And if UE4, assuming the linking step is very fast, does that re-linking over and over, very often, what you end up with is horrible pipeline compilation stutter every few seconds. And in this case, it’s not really UE’s fault, even! Sorry for that, Unreal.

Clearly, inlining all the any-hit and intersection shaders won’t work. So why not just compile them separately?

To answer that, I’ll try to start with explaining some assumptions that lie at the base of RADV’s shader compilation. When ACO (and NIR, too) were written, shaders were usually incredibly simple. They had some control flow, ifs, loops and whatnot, but all the code that would ever execute was contained in one compact program executing top-to-bottom. This perfectly matched what graphics/compute shaders looked like in the APIs, and what the API does is what you want to optimize for.

Unfortunately, this means RADV’s shader compilation stack got hit extra hard by the paradigm shift introduced by RT pipelines. Dynamic linking of different programs, and calls across the dynamic link boundaries, is something common in CPU programming languages (C/C++, etc.), but Mesa never really had to deal with something like that before2.

One specific core assumption that prevents us from compiling any-hit/intersection shaders separately just like that is that every piece of code assumes it has exclusive and complete access to things like registers and other hardware resources. Comparing to CPU again, most of the program code is contained in some functions, and those functions will be called from somewhere else3. Those functions will have used CPU registers and stack memory and so on before, and code inside that function can’t write to just any CPU register, or any location on stack. Which registers are writable by a function and which ones must have their values preserved (so that the function callers can store values of their own there without them being overwritten) are governed by little specifications called “calling conventions”.

In Mesa, the shader compiler generally used to have no concept of calling conventions, or a concept of “calling” something, for that matter. There was no concept of a register having some value from a function caller and needing to be preserved - if a register exists, the shader might end up writing its own value to it. In cases of graphics/compute shaders, this wasn’t a problem - the registers only ever had random uninitialized values in them.

This has always been a problem for separately compiling shaders in RT pipelines, but we had a different solution: At every point a shader called another shader, we’d split the shader in half: One half containing everything before the call, and the other half containing everything after. Of course, sometimes the second half needed variables coming from the first half of the shader. All these variables would be stored to memory in the first half. Then, the first half ends, and execution jumps to the called shader. Once the end of the called shader is reached, execution returns to the second half.

This was good enough for things like calling into traceRay to trace a ray and execute all the associated closest hit/miss shaders. Usually, applications wouldn’t

have that many variables needing to be backed up to memory, and tracing a ray is supposed to be expensive.

But that concept completely breaks down when you apply it to any-hit shaders. At the point an any-hit shader is called, you’re right in the middle of ray traversal. Ray traversal has lots of internal state variables that you really want to keep in registers at all times. If you call an any-hit shader with this approach, you’d have to back up all of these state variables to memory and reload them back afterwards. Any-hit shaders are supposed to be relatively cheap and called potentially lots of times during traversal. All these memory stores and reloads you’d need to insert would completely ruin performance.

So, separately compiling any-shaders was an absolute no-go. At least, unless someone were to go off the deep end and change the entire compiler stack to fix the assumptions at their heart.

I went and changed more or less the entire compiler stack to fix these assumptions and introduce proper function calls.

The biggest part of this work by far were the absolute basics. How do we best teach the compiler that certain registers need to be preserved and are best left alone? How should the compiler figure out that something like a call instruction might randomly overwrite other registers? How do we represent a calling convention/ABI specification in the driver? All of these problems can be tackled with different approaches and at different stages of compilation, and nailing down a clean solution is pretty important in a rework as fundamental as this one.

I started out with applying function calls to the shaders that were already separately compiled - this means that the function call work itself didn’t improve performance by too much, but in retrospect I think it was a very good idea to make sure the baseline functionality is rock-solid before moving on to separately-compiling any-hit shaders.

Indeed, once I finally got around to adding the code that splits out any-hit/intersection shaders and use function calls for them, things worked nearly out of the box! I opened the associated merge request a bit over two weeks ago and got everything merged within a week. (Of course, I would never have gotten it in that fast without all the reviewers teaming up to get everything in ASAP! Big thank you to Daniel, Rhys and Konstantin)

In comparison, I started work on function calls in January of 2024 and got the initial code in a good enough shape to open a merge request in June that year, and the code only got merged on the same day I opened the above merge request, two years after starting the initial drafting (although to be fair, that merge request also had periods of being stalled due to personal reasons).

Function calls makes shader compilation work in arguably a much more straightforward way. For the most part, the shader just gets compiled like any other -

there’s no fancy splitting or anything going on. If a shader

calls another shader, like when executing traceRay, or when calling an any-hit shaders, a call instruction is generated. When the called shader finishes,

execution resumes after the call instruction.

All the magic happens in ACO, the compiler backend. I’ve documented the more technical design of how calls and ABIs are represented in

a docs article.

At first, call instructions in the NIR IR are translated to a p_call “pseudo” instruction. It’s not actually a hardware instruction, but serves as a

placeholder for the eventual jump to the callee. This instruction also carries information about which specific registers parameters will be stored in, and

which registers may be overwritten by the call instruction.

ACO’s compiler passes have special handling for calls wherever necessary: For example, passes analyzing how many registers are required in all the different parts of the code take special care to take into account that in call instructions, fewer registers may be available to store values in (because all other values are overwritten). ACO also has a spilling pass for moving register values to memory whenever the amount of used registers exceeds the available amount.

Another fundamental change is that function calls also introduce a call stack. In CPUs, this is no big deal - you have one stack pointer register, and it points to the stack region that your program uses. However, on GPUs, there isn’t just one stack - remember that GPUs are highly parallel, and every thread running on the GPU needs its own stack!

Luckily, this sounds worse at first than it actually is. In fact, the hardware already has facilities to help manage stacks. AMD GPUs ever since Vega4 have

the concept of “scratch memory” - a memory pool in VRAM where the hardware ensures that each thread has its own private “scratch region”. There are special

scratch_* memory instructions that load and store from this scratch area. Even though they’re also VRAM loads/stores, they don’t take any address, just an offset,

and for each thread return the value stored in that thread’s own scratch memory region.

In my blog post about RT pipeline being enabled by default I claimed AMD GPUs don’t implement a call stack.

This is actually misleading - the scratch memory functionality is all you need to implement a stack yourself. The “stack pointer” here is just the offset

you pass to the scratch_* memory instruction. Pushing to the stack increases the stack offset, and popping from it decreases the offset5.

Eventually, when it comes to converting a call to hardware instructions, all that is needed is to execute the s_swappc instruction. This instruction

automatically writes the address of the next instruction to a register before jumping to the called shader. When the called shader wants to return, it

merely needs to jump to the address stored in that register, and execution resumes from right after the call instruction.

Finally, any-hit separate compilation was a straightforward task as well - it was merely an issue of defining an ABI that made sure that a ton of registers stay preserved and the caller can stash its values there. In practice, all of the traversal state will be stashed in these preserved registers. No expensive spilling to memory needed, just a quick jump to the any-hit shader and back.

If you look at the merge request, the performance benefits seem pretty obvious.

Ghostwire Tokyo’s RT passes speed up by more than 2x, and of course pipeline compilation times improved massively.

The compilation time difference is quite easy to explain. Generally, compilers will perform a ton of analysis passes on shader code to find everything they can to optimize it to death. However, these analysis passes often require going over the same code more than once, e.g. after gathering more context elsewhere in the shader. This also means that a shader that doubles in size will take more than twice as long to compile. When inlining hundreds or thousands of shaders into one, that also means that shader’s compile time grows by a lot more than just a hundred or a thousand times.

Thus, if we reverse things and are suddenly able to stop inlining all the shaders into one, that scaling effect means all the shaders will take less total time to compile than the one big megashader. In practice, all modern games also offload shader compilation to multiple threads. If you can compile the any-hit shaders separately, the game can compile them all in parallel - this just isn’t possible with the single megashader which will always be compiled on a single thread.

In the runtime performance department, moving to just having a single call instruction instead of hundreds of shaders in one place means the loop has a much smaller code size. In a loop iteration where you don’t call any any-hit shaders, you would still need to jump over all of the code for those shaders, almost certainly causing instruction cache misses, stalls and so on.

Also, forcing any-hit/intersection shaders to be separate also means that any-hit/intersection shaders that consume tons of registers despite nearly never getting called won’t have any negative effects on ray traversal as a whole. ACO has heuristics on where to optimally insert memory stores in case something somewhere needs more registers than available. However, these heuristics may decide to insert memory stores inside the generic traversal loop, even if the problematic register usage only comes from a few rarely-called inlined shaders. These stores in the generic loop would now mean that the whole shader is slowed down in every case.

However, separate compilation doesn’t exclusively have advantages, either. In an inlined shader, the compiler is able to use the context surrounding the (now-inlined) shader to optimize the code itself. A separately-compiled shader needs to be able to get called from any imaginable context (as long as it conforms to ABI), and this inhibits optimization.

Another consideration is that the jump itself has a small cost (not as big as you’d think, but it does have a cost). RADV currently keeps inlining any-hit shaders as long as you don’t have too many of them, and as long as doing so wouldn’t inhibit the ability to compile the shaders in parallel.

I also openend a merge request that provided massive performance improvements to Lumen’s RT right before the branchpoint.

However, these improvements are completely unrelated to function calls. In fact, they’re a tiny bit embarrassing, because all that changed was that RADV doesn’t make the hardware do ridiculously inefficient things anymore.

Let’s talk about dispatching RT shaders. The Vulkan API provides a vkCmdTraceRaysKHR command that takes in the number of rays to dispatch for X, Y and Z

dimensions. Usually, compute dispatches are described in terms of how many thread groups to dispatch, but RT is special because one ray corresponds to one

thread. So here, we really get the dispatch sizes in threads, not groups.

By itself, that’s not an issue. In fact, AMD hardware has always been able to specify dispatch dimensions in threads instead of groups. In that case, the hardware takes the job of assembling just enough groups that hold the specified number of threads. The issue here comes from how we describe that group to the hardware. The workgroup size itself is also per-dimension, and the simplest case of 32x1x1 threads (i.e. a 1D workgroup) is actually not always the best.

Let’s consider a very common ray tracing use case: You might want to trace a ray for each pixel in a 1920x1080 image. That’s pretty easy, you just call

vkCmdTraceRaysKHR to dispatch 1920 rays in the X dimension and 1080 in the Y dimension.

When you dispatch a 32x1x1 workgroup, the coordinates for each thread in a workgroup look like this:

thread id | 0 | 1 | 2 | ... | 16 | 17 |...| 31 |

coord |(0,0)|(1,0)|(2,0)| ... |(16,0)|(17,0)|...|(31,0)|

Or, if you consider how the thread IDs are laid out in the image:

-------------------

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ..

-------------------

That’s a straight line in image space. That’s not the best, because it means that the pixels will most likely cover different objects which may have very different trace characteristics. This means divergence during RT will be higher, which can make the overall process slower.

Let’s look instead what happens when you make the workgroup 2D, with a 8x4 size:

thread id | 0 | 1 | 2 | ... | 16 | 17 |...| 31 |

coord |(0,0)|(1,0)|(2,0)| ... |(0,2) |(1,2) |...|(7,3) |

In image space:

-------------------

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ..

------------------

8 | 9 | 10| 11| ..

------------------

16| 17| 18| 19| ..

-------------------

That’s much better. Threads are now arranged in a little square, and these squares are much more likely to all cover the same objects, have similar RT characteristics, etc.

This is why RADV used 8x4 workgroups as well. Now let’s get to when this breaks down. What if the RT dispatch doesn’t actually have 2 dimensions? What if there are 1920 rays in the X dimension, but the Y dimension is just 1?

It turns out that the hardware can only run 8 threads in a single wavefront in this case. This is because the rest of the workgroup is out-of-bounds of the dispatch - it has a non-zero Y coordinate, but the size in the Y dimension is only 1, so it would exceed the dispatch bounds.

The hardware also can’t pull in threads from other workgroups, because one wavefront can only ever execute one workgroup. The end result is that the wave runs with only 8 out of 32 threads active - at 1/4 theoretical performance. For no real reason.

I actually had noticed this issue years ago (with UE4, ironically). Back then I worked around it by rearranging the game’s dispatch sizes into a 2D one behind its back, and recalculating a 1-dimensional dispatch ID inside the RT shader so the game doesn’t notice. That worked just fine… as long as we’re actually aware about the dispatch sizes.

UE5 doesn’t actually use vkCmdTraceRaysKHR. It uses vkCmdTraceRaysIndirectKHR, a variant of the command where the dispatch size is read from GPU memory, not

specified on the CPU. This command is really cool and allows for some and nifty GPU-driven rendering setups where you only dispatch as many rays as

you’re definitely going to trace (as determined by previous GPU commands). This command also rips a giant hole in the approach of rearranging dispatch sizes, because

we don’t even know the dispatch size before the dispatch is actually executed. That means the super simple workaround I built was never hit, and we had the same

embarrassingly inefficient RT performance as a few years ago all over again.

Obviously, if UE5 is too smart for your workaround, then the solution is to make an even smarter workaround. The ideal solution would work with a 1D thread ID (so that we don’t run into any more issues when there is a 1D dispatch, but if a 2D dispatch is detected, we turn that “line” of 1D IDs into a “square”. The whole idea about turning a linear coordinate into a square reminded me a lot of how Z-order curves work. In fact, the GPU arranges things like image data on a Z-order curve by interleaving the address bits from X and Y already, because nearby pixels are often accessed together and it’s better if they’re close to each other.

However, instead of interleaving a X and Y coordinate pair to make a linear memory address, we want the opposite: We have a linear dispatch ID, and we want to recover a 2D coordinate inside a square from it. That’s not too hard, you just do the opposite operation: Deinterleave the bits, where every odd/even bit of the dispatch ID forms the X/Y coordinate. As it turned out, you can actually do this entirely from inside the shader with just a few bit twiddling tricks, so this approach work for both indirect and direct (non-indirect) trace commands.

With that approach, dispatch IDs and coordinates look something like this:

thread id | 0 | 1 | 2 | ... | 16 | 17 |...| 31 |

coord |(0,0)|(1,0)|(0,1)| ... |(4,0) |(5,0) |...|(7,3) |

In image space:

-------------------

0 | 1 | 4 | 5 | ..

------------------

2 | 3 | 6 | 7 | ..

------------------

8 | 9 | 12| 13| ..

-------------------

10| 11| 14| 15| ..

-------------------

Not only are the thread IDs now arranged in squares, the squares themselves get recursively subdivided into more squares! I think theoretically this should be a further improvement w.r.t divergence, but I don’t think it has resulted in measurable speedup in practice anywhere.

The most important thing, though, is that now UE5 RT doesn’t run 4x slower than it should. Oops.

The second most fun thing about function calls is that you can just jump to literally any program anywhere, provided the program doesn’t completely thrash your preserved registers and stack space.

The most fun thing about function calls is what happens when the program does just that.

I’m going to use this section to scream in the void about two very real function call bugs that were reported after I already merged the MR. This is not an exhaustive list, you can trust I’ve had much much more fun just like what I’ll be presenting here while I was testing and developing function calls.

On the scale of function call bugs, this one was rather tame, even. Having infinite loops isn’t the most optimal for hang debugging, but it does mean that you can use a tool like umr to sample

which wavefronts are active, and get some register dumps. The program counter will at least point to some instruction in the loop that it’s stuck in, and you can get yourself the disassembly

of the whole shader to try and figure out what’s going in the loop and why the exit conditions aren’t met.

The loop in Avowed was rather simple: It traced a ray in a loop, and when the loop counter was equal to an exit value, control flow would break out of the loop. The register dumps also immediately highlighted the loop exit counter being random garbage. So far so good.

During the traceRay call, the loop exit counter was backed up to the shader’s stack. Okay, so it’s pretty obvious that the stack got smashed somehow and that corrupted the loop exit counter.

What was not obvious, however, was what smashed the stack. Debugging this is generally a bit of an issue - GPUs are far, far away from tools like AddressSanitizer, especially at a compiler level. There are no tools that would help me catch a faulty access at runtime. All I could really do was look at all the shaders in that ray tracing pipeline (luckily that one didn’t have too many) and see if they somehow store to wrong stack locations.

All shaders in that pipeline were completely fine, though. I checked every single scratch instruction in every shader if the offsets were correct (luckily, the offsets are constants encoded in the disassembly, so this part was trivial). I also verified that the stack pointer was incremented by the correct values - everything was completely fine. No shader was smashing its callers’ stack.

I found the bug more or less by complete chance. The shader code was indeed completely correct, there were no miscompilations happening. Instead, the “scratch memory” area the HW allocated was smaller than what each thread actually used, because I forgot to multiply by the number of threads in a wavefront in one place.

The stack wasn’t smashed by the called function, it was smashed by a completely different thread. Whether your stack would get smashed was essentially complete luck, depending on where the HW placed your scratch memory area, other wavefront’s scratch, and how those wavefronts’ execution was timed relative to yours. I don’t think I would ever have been able to deduce this from any debugger output, so I should probably count myself lucky I stumbled upon the fix regardless.

Did I talk about Unreal Engine yet? Let’s talk about Unreal Engine some more. Silent Hill 2 uses Lumen for its reflection/GI system, and somehow Lumen from UE 5.3 specifically was the only thing that seemed to reproduce this particular bug.

In every way the Avowed bug was tolerable to debug, this one was pure suffering. There were no GPU hangs, all shaders ran completely fine. That means using umr and getting

a rough idea of where the issue is was off the table from the start. Unfortunately, the RT pipeline was also way too large to analyze - there were a few hundred hit shaders,

but there also were seven completely different ray generation shaders.

Having little other recourse, I started trying to at least narrow down the ray generation shader that triggered the fault. I used Mesa’s debugging environment variables to

dump the SPIR-V of all the shaders the driver encountered, and then used spirv-cross on all of them to turn them into editable GLSL. For each ray generation shader, I’d

comment out the imageStore instructions that stored the RT result to some image, recompiled the modified GLSL to SPIR-V, and instructed Mesa to sneakily swap out the original

ray-gen SPIR-V with my modified one. Then I re-ran the game to see if anything changed.

This indeed led me to find the correct ray generation shader, but the lead turned into a dead end - there was little insight other than that the ray was indeed executing the miss shader. Everything seemed correct so far, and if I hadn’t known these rays didn’t miss about 3 commits ago, I honestly wouldn’t even have suspected anything was wrong at all.

The next thing I tried was commenting out random things in ray traversal code. Skipping over all any-hit/intersection shaders yielded no change, and neither did replacing the ray flags/culling masks with known good constants to rule out wrong values being passed as parameters. What did “fix” the result, however, was… commenting out the calls to closest-hit shaders.

Now, if closest-hit shaders get called and that makes miss shaders execute somehow, you’d perhaps think we’d be calling the wrong function. Maybe we confuse the shader binding table where we load the addresses of shaders to call from? To verify that assumption, I also disabled calling any and all miss shaders. I zeroed out the addresses in the shader handles to make extra sure there was no possible way that a miss shader could ever get called. To keep things working, I replaced the code that calls miss shaders with the relevant code fragment from UE’s miss shader (essentially inlining the shader myself).

Nothing changed from that. That means a closest-hit shader being executed somehow resulted in a ray traversal itself returning a miss, not the wrong function being called.

Perhaps the closest-hit shaders corrupt some caller values again? Since the RT pipeline was too big to analyze, I tried to narrow down the suspicious shaders by only disabling specific closest-hit shaders. I also discovered that just making all closest-hit shaders no-ops “fixed” things as well, even if they do get called.

Sure enough, at some point I had a specific closest-hit shader where the issue went away once I deleted all code from it/made it a no-op. I even figured out a specific register that, if explicitly preserved, would make the issue go away.

The only problem was that this register corresponded to one part of the return value of the closest-hit shader - that is, a register that the shader was supposed to overwrite.

From here on out it gets completely nonsensical. I will save you the multiple days of confusion, hair-pulling, desperation and agony over the complete and utter undebuggableness of Lumen’s RT setup and skip to the solution:

It turned out the “faulty” closest-hit shader I found was nothing but a red herring. Lumen’s RT consists of 6+ RT dispatches, most of which I haven’t exactly figured out the purpose of, but what

I seemed to observe was that the faulty RT dispatch used the results of the previous RT dispatch to make decisions on whether to trace any rays or not. Making the closest-hit shaders a no-op

did nothing but disable the subsequent traceRays that actually exhibited the issue.

Since these RT dispatches used the same RT pipelines, that meant virtually any avenue I had of debugging this driver-side was completely meaningless. Any hacks inside the shader compiler might actually work around the issue, or just affect a conceptually unrelated dispatch that happens to disable the actually problematic rays. Determining which was the case was nearly impossible, especially in a general case.

I never really figured out how to debug this issue. Once again, what saved me was a random epiphany out of the blue. In fact, now that I know what the bug was, I’m convinced I would’ve never found this through a debugger either.

The issue turned out to be in an optimization for what’s commonly called tail-calls. If you have a function that calls another function at the very end just before returning, a common optimization is to simply turn that call into a jump, and let the other function return directly to the caller.

Imagine ray traversal working a bit like this C code:

/* hitT is the t value of the ray at the hit point */

payload closestHit(float hitT);

/* tMax is the maximum range of the ray, if there is

* no hit with a t <= tMax, the ray misses instead */

payload traversal(float tMax) {

do something;

if (hit)

return closestHit(hitT); // gets replaced with a jmp, closestHit returns directly to traversal's caller

}

More specifically, the bug was with how preserved parameters and tail-calls interact. Function callers are generally supposed to assume that preserved parameters do not change their value over the function call. That means it’s safe to reuse that register after the call and assuming it still has the value the caller put in.

However, in the example above, let’s assume closestHit has the same calling convention as traversal. That means closestHit’s parameter needs to go into the same register as traversal’s parameter, and thus the register

gets overwritten.

If traversal’s caller was assuming that the parameter is preserved, that would mean the value of tMax has just been overwritten with the value of hitT without the caller knowing.

If traversal now gets called again from the same place, the value of tMax is not the intended value, but the hitT value from the previous iteration, which is definitely smaller than tMax.

Put shortly: If all these conditions are met, a smaller-than-intended tMax could cause rays to miss when they were intended to hit.

Once again, I got incredibly lucky and stumbled upon the bug by complete chance.

The GPU gods seem to be in good spirits for my endeavours. I pray it stays this way.

“Shader” in this context really means any program that runs on the GPU. The RT pipeline is also made of shaders, shaders determine where the points and triangles making up each object end up on screen, there are compute shaders for generic computing, and so on… ↩

There actually is another use-case where this becomes relevant on GPU - and that is GPGPU code like CUDA/HIP/OpenCL. CUDA/HIP allow you to write C++ for the GPU in a much more “CPU-like” programming environment (OpenCL uses C), and you run into all the same problems there. This also means all the major GPU vendors had already written their solutions for these problems when raytracing came around. There are OpenCL kernels that end up really really bad if you don’t have proper function calls in the compiler (which Rusticl suffers from right now), and the function calls work in RADV/ACO may end up proving useful for those as well. ↩

Even your main function works like that, actually. Unless you have some form of freestanding environment, all your program code works like that. ↩

In RADV, the stack pointer is actually constant across a function, and pushing/popping to/from the stack is implemented by adding another offset to the constant stack pointer in load/store instructions. This allows to make the stack pointer an SGPR instead of a VGPR and simplifies stack accesses that aren’t push/pop. ↩

We support raytracing before Vega too. We support function calls on all GPUs, as well, through a little magic in dreaming up a buffer descriptor with specific memory swizzling to achieve the same addressing that scratch_* instructions use on Vega and later. ↩

Today, we announce Amutable, our ✨ new ✨ company. We – @blixtra@hachyderm.io, @brauner@mastodon.social, @davidstrauss@mastodon.social, @rodrigo_rata@mastodon.social, @michaelvogt@mastodon.social, @pothos@fosstodon.org, @zbyszek@fosstodon.org, @daandemeyer@mastodon.social @cyphar@mastodon.social, @jrocha@floss.social and yours truly – are building the 🚀 next generation of Linux systems, with integrity, determinism, and verification – every step of the way.

For more information see → https://amutable.com/blog/introducing-amutable

Today is a big day for graphics. We got shiny new extensions and a new RM2026 profile, huzzah.

VK_EXT_descriptor_heap is huge. I mean in terms of surface area, the sheer girth of the spec, and the number of years it’s been under development. Seriously, check out that contributor list. Is it the longest ever? I’m not about to do comparisons, but it might be.

So this is a big deal, and everyone is out in the streets (I assume to celebrate such a monumental leap forward), and I’m not.

All hats off. Person to person, let’s talk.

It’s true that descriptor heap is incredibly powerful. It perfectly exemplifies everything that Vulkan is: low-level, verbose, flexible. vkd3d-proton will make good use of it (eventually), as this more closely relates to the DX12 mechanics it translates. Game engines will finally have something that allows them to footgun as hard as they deserve. This functionality even maps more closely to certain types of hardware, as described by a great gfxstrand blog post.

There is, to my knowledge, just about nothing you can’t do with VK_EXT_descriptor_heap. It’s really, really good, and I’m proud of what the Vulkan WG has accomplished here.

But I don’t like it.

It’s a risky position; I don’t want anyone’s takeaway to be “Mike shoots down new descriptor extension as worst idea in history”. We’re all smart people, and we can comprehend nuance, like the difference between rb and ab in EGL patch review (protip: if anyone ever gives you an rb, they’re fucking lying because nobody can fully comprehend that code).

In short, I don’t expect zink to ever move to descriptor heap. If it does, it’ll be years from now as a result of taking on some other even more amazing extension which depends on heaps. Why is this, I’m sure you ask. Well, there’s a few reasons:

Like all things Vulkan, “getting it right” with descriptors meant creating an API so verbose that I could write novels with fewer characters than some of the struct names. Everything is brand new, with no sharing/reuse of any existing code. As anyone who has ever stepped into an unfamiliar bit of code and thought “this is garbage, I should rewrite it all” knows too well, existing code is always the worst code–but it’s also the code that works and is tied into all the other existing code. Pretty soon, attempting to parachute in a new descriptor API becomes rewriting literally everything because it’s all incompatible. Great for those with time and resources to spare, not so great for everyone else.

Gone are image views, which is cool and good, except that everything else in Vulkan still uses them, meaning now all image descriptors need an extra pile of code to initialize the new structs which are used only for heaps. Hope none of that was shared between rendering and descriptor use, because now there will be rendering use and descriptor use and they are completely separate. Do I hate image views? Undoubtedly, and I like this direction, but hit me up in a few more years when I can delete them everywhere.

Shader interfaces are going to be the source of most pain. Sure, it’s very possible to keep existing shader infrastructure and use the mapping API with its glorious nested structs. But now you have an extra 1000 lines of mapping API structs to juggle on top. Alternatively, you can get AI to rewrite all your shaders to use the new spirv extension and have direct heap access.

Descriptor heap maps closer to hardware, which should enable users to get more performant execution by eliminating indirection with direct heap access. This is great. Full stop.

…Unless you’re like zink, where the only way to avoid shredding 47 CPUs every time you change descriptors is to use a “sliding” offset for descriptors and update it each draw (i.e., VK_DESCRIPTOR_MAPPING_SOURCE_HEAP_WITH_PUSH_INDEX_EXT). Then you can’t use direct heap access. Which means you’re still indirecting your descriptor access (which has always been the purported perf pain point of 1.0 descriptors and EXT_descriptor_buffer). You do not pass Go, you do not collect $200. All you do is write a ton of new code.

There’s a tremendous piece of exposition outlining the reasons why EXT_descriptor_heap exists in the proposal. None of these items are incorrect. I’ve even contributed to this document. If I were writing an engine from scratch, I would certainly expect to use heaps for portability reasons (i.e., in theory, it should eventually be available on all hardware).

But as flexible and powerful as descriptor heap is, there are some annoying cases where it passes the buck to the user. Specifically, I’m talking about management of the sampler heap. 1.0 descriptors and descriptor buffer just handwave away the exact hardware details, but with VK_EXT_descriptor_heap, you are now the captain of your own destiny and also the manager of exactly how the hardware is allocating its samplers. So if you’re on NVIDIA, where you have exactly 4096 available samplers as a hardware limit, you now have to juggle that limit yourself instead of letting the driver handle it for you.

This also applies to border colors, which has its own note in the proposal. At an objective, high-view level, it’s awesome to have such fine-grained control over the hardware. Then again, it’s one more thing the driver is no longer managing.

That’s certainly the takeaway here. I’m not saying go back to 1.0 descriptors. Nobody should do that. I’m not saying stick with descriptor buffers either. Descriptor heap has been under development since before I could legally drive, and I’m certainly not smarter than everyone (or anyone, most likely) who worked on it.

Maybe this is the best we’ll get. Maybe the future of descriptors really is micromanaging every byte of device memory and material stored within because we haven’t read every blog post in existence and don’t trust driver developers to make our shit run good. Maybe OpenGL, with its drivers that “just worked” under the hood (with the caveat that you, the developer, can’t be an idiot), wasn’t what we all wanted.

Maybe I was wrong, and we do need like five trillion more blog posts about Vulkan descriptor models. Because releasing a new descriptor extension is definitely how you get more of those blog posts.

Hi!

Last week I’ve released Goguma v0.9! This new version brings a lot of niceties, see the release notes for more details. New since last month are audio previews implemented by delthas, images for users, channels & networks, and usage hints when typing a command. Jean THOMAS has been hard at work to update the iOS port and publish Goguma on AltStore PAL.

It’s been a while since I’ve started a NPotM, but this time I have something new to show you: nagjo is a small IRC bot for Forgejo. It posts messages on activity in Forgejo (issue opened, pull request merged, commits pushed, and so on), and it expands references to issues and pull requests in messages (writing “can you look at #42?” will reply with the issue’s title and link). It’s very similar to glhf, its GitLab counterpart, but the configuration file enables much more flexible channel routing. I hope that bot can be useful to others too!

Up until now, many of my projects have moved to Codeberg from SourceHut, but the issue tracker was still stuck on todo.sr.ht due to a lack of a migration tool. I’ve hacked together srht2forgejo, a tiny script to create Forgejo issues and comments from a todo.sr.ht archive. It’s not perfect since the author is the migration user’s instead of the original one, but it’s good enough. I’ve now completely migrated all of my projects to Codeberg!

I’ve added a server implementation and tests to go-smee, a small Go library for a Web push forwarding service. It comes in handy when implementing Web push receivers because it’s very simple to set up, I’ve used it when working on nagjo.

I’ve extended the haproxy PROXY protocol to add a new client certificate TLV to relay the raw client certificate from a TLS terminating reverse proxy to a backend server. My goal is enabling client certificate authentication when the soju IRC bouncer sits behind tlstunnel. I’ve also sent patches for the kimchi HTTP server and go-proxyproto.

Because sending a haproxy patch involved git-send-email, I’ve noticed I’ve

started hitting a long-standing hydroxide signature bug when sending a

message. I wasn’t previously impacted by this, but some users were. It took a

bit of time to hunt down the root cause (some breaking changes in ProtonMail’s

crypto library), but now it’s fixed.

Félix Poisot has added two new color management options to Sway: the

color_profile command now has separate gamma22 and srgb transfer

functions (some monitors use one, some use the other), and a

--device-primaries flag to read color primaries from the EDID (as an

alternative to supplying a full ICC profile).

With the help of Alexander Orzechowski, we’ve fixed multiple wlroots issues regarding toplevel capture (aka. window capture) when the toplevel is completely hidden. It should all work fine now, except one last bug which results in a frozen capture if you’re unlucky (aka. you loose the race).

I’ve shipped a number of drmdb improvements. Plane color pipelines are now

supported and printed on the snapshot tree and properties table. A warning icon

is displayed next to properties which have only been observed on tainted or

unstable kernels (as is usually the case for proprietary or vendor kernel

modules with custom properties). The device list now shows vendor names for

platform devices (extracted from the kernel table). Devices using the new

“faux” bus (e.g. vkms) are now properly handled, and all of the possible cursor

sizes advertised via the SIZE_HINTS property are now printed. I’ve also done

some SQLite experiments, however they turned out unsuccessful (see that

thread and the merge request for more details).

delthas has added a new allow_proxy_ip directive to the kimchi

HTTP server to mark IP addresses as trusted proxies, and has made it so

Forwarded/X-Forwarded-For header fields are not overwritten when the

previous hop is a trusted proxy. That way, kimchi can be used in more scenario:

behind another HTTP reverse proxy, and behind a TCP proxy which doesn’t have a

loopback IP address (e.g. tlstunnel in Docker).

See you next month!

So one thing I think anyone involved with software development for the last decades can see is the problem of “forest of bogus patents”. I have recently been trying to use AI to look at patents in various ways. So one idea I had was “could AI help improve the quality of patents and free us from obvious ones?”

Lets start with the justification for patents existing at all. The most common argument for the patent system I hear is this one : “Patents require public disclosure of inventions in exchange for protection. Without patents, inventors would keep innovations as trade secrets, slowing overall technological progress.”. This reasoning is something that makes sense to me, but it is also screamingly obvious to me that for it to hold true you need to ensure the patents granted are genuinely inventions that otherwise would stay hidden as trade secrets. If you allow patents on things that are obvious to someone skilled in the art, you are not enhancing technological progress, you are hampering it because the next person along will be blocking from doing it.

So based on this justification the question then becomes does for example the US Patents Office do a good job filtering out obvious patents? And I believe the answer is “No they don’t”. Having been working in the space of software for many decades now it is very clear to me that the patent office do very little to avoid patents getting approved for obvious things. And there are many reasons for why that happens I think. First of all if you are an expert in a field you would likely not be working as a case worker in the patent office, no disrespect for the people working there, but for instance if you are a really good software engineer there are much better paying options to be found elsewhere, same goes for medical researchers for example. So we have people who have limited understanding of the field of the patent trying to evaluate if the patent is obvious or not.

Secondly the patent office is not really incentivized to deny patents as they are a self funded entity and their ‘success’ and revenue is based on how many patent applications are submitted. So the lower the bar of approval, the more patents applications get submitted and thus the patent office makes more money and is more “successful”. This is a problem, but maybe if we fix the first issue I mention it is maybe possible to reduce the impact of this second issue.

So what can AI do to help here? It can help patent reviewers at the patent office with evaluating patents for obviousness due to having been trained on these fields. If we required every patent applied for to be run through a AI engine for review then the patent office reviewer would have to justify why he or she believes something is non-obvious after the AI has looked at it and concluded it is not. My assumption would be that they would very rarely do so.

To test out this I decided to ask Gemini to review a H264 video patent that is still valid and which has been used in litigation before, to see if it could do a decent job of reviewing the patent application and judge if this is a true invention or not. Here is what Gemini came up with.

US Patent 7,916,782 (Samsung Electronics) is one of the most famous “battleground” patents in the history of smartphone litigation. It has been asserted against Apple, Huawei, and others.

It covers a specific part of the H.264 standard known as CAVLC (Context-Adaptive Variable Length Coding).

The Patent: US 7,916,782 : Method and apparatus for video coding and decoding The Mechanism: Efficiently coding the count of zero-valued pixels in a video block (“TotalZeros”).

The Problem

In video compression, you divide the image into small 4×4 pixel blocks. After processing (transform and quantization), most of the 16 pixels in the block end up being zero. You only have a few non-zero numbers left.

Goal: You need to tell the decoder how many zeros are in the block so it can reconstruct the empty space.

Constraint: You already told the decoder how many non-zero coefficients exist (let’s say you have 5 non-zeros).

The “Invention” The patent claims a method where the encoder selects a specific lookup table (VLC table) to encode the “TotalZeros” value, and—crucially—this selection is based on the number of non-zero coefficients (TotalCoeff) that were just processed. If TotalCoeff is 1, use Table A (allows for many zeros).If TotalCoeff is 10, use Table B (allows for fewer zeros).

The “Skilled Engineer” Test

Imagine you are a video coding engineer in 2002. You are tasked with compressing the “TotalZeros” value. Here is the logical deduction chain you would inevitably follow: